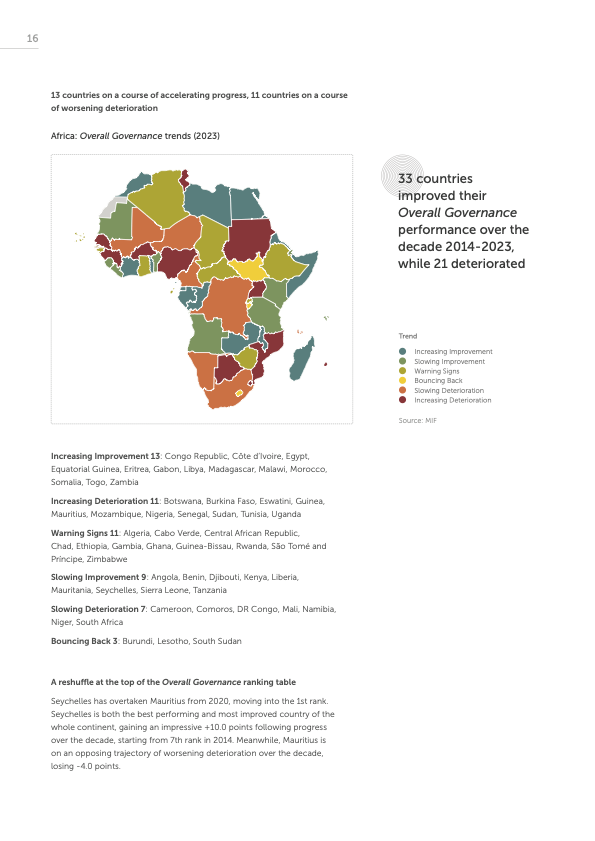

The African governance landscape has constituted a mix of progress and setbacks in the recent decade. Diverse national trajectories, including the growing role of digital technology, shaped the variation. While some countries have made impressive overall governance gains, others continue to struggle and decline. The 2024 Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG) highlights these realities. The report shows that although over half of African nations have improved in key areas, the overall governance state on the continent points to stagnation over the past decade. In particular, civic participation, rights, and inclusion are observed to be on the decline, signalling a growing disconnect between citizens and the institutions meant to serve them (Mo Ibrahim Foundation, 2024).

Citizens are more likely to trust the outcome of state decision-making when they are meaningfully engaged in the process. This emphasises how crucial civic engagement is to the right to a robust democracy. These democratic principles are threatened, nevertheless, by a decreasing civic space. Resulting in increasing social instability and the erosion of public trust. This concern is even more pressing given Africa’s projected urban growth and shifting demographics. Africa’s urban population is growing and is expected to reach 60 per cent by 2050, and governments face mounting pressure to deliver services, create jobs, and ensure stability (African Union, 2024).

The African governance landscape has constituted a mix of progress and setbacks in the recent decade. Diverse national trajectories, including the growing role of digital technology, shaped the variation.

The challenge is that urbanisation is outpacing economic growth, widening the gap between rising populations and essential services. High unemployment, informality, and trends like gentrification and debt-driven infrastructure projects further complicate governance (Kamana, Radoine & Nyasulu, 2024). Too often, governments prioritise economic growth over inclusive governance, deepening the disconnect between citizens and the state. Additionally, by 2050, the continent’s population is projected to hit 2.5 billion, with youth aged 15–24 making up over 34 per cent (UN DESA, 2024; Bekele-Thomas & Westgaard, 2024). This younger, increasingly urban population relies on digital platforms not just for education, employment, and entrepreneurship but also for political expression. Movements such as Kenya’s 2024 #FinanceBillProtests and Nigeria’s EndSARS campaign illustrate how digital tools empower citizens to demand accountability (Amnesty International, 2021; Twinomurinzi, 2024).

Urban Africa in the Digital Age: Governance, Growth, and Gaps

The digital transformation across urban Africa is bringing exciting solutions to governance and development. Although this transformation is not uniform across the continent, neither is it without its challenges. As African cities grow into centres of political and economic activity, digital technologies are increasingly showing potential in improving service delivery, boosting civic engagement, and tackling urban issues. However, digital transformation in urban Africa must address existing infrastructural and social limitations so that these innovations do not end up worsening the urban experiences of already marginalized communities. Some of such issues include infrastructure gaps, historical and urban inequalities, policy inconsistencies, and ethical concerns.

Globally, the Internet of Things (IoT), artificial intelligence (AI), and blockchain technologies are increasingly reshaping governance in general. In cities like Nairobi, IoT sensors and AI are used in the monitoring and advancement of transport systems (Mahugu and Mambo, 2024). AI-driven analytics now enable municipalities to better predict and respond to disasters like flooding, as such improving their disaster management plans (Martin, 2024). The projected urban population growth of African cities, which points to an increased state of infrastructural constraints, informality, and unemployment, makes these sorts of technological innovations critical for sustainable and inclusive development on the continent.

Digital platforms and technologies have the potential to open up participatory spaces and improve public engagement.

Digital platforms and technologies have the potential to open up participatory spaces and improve public engagement. Consequently improving transparency, accessibility, and accountability in state and urban governance. For instance, in Kenya, participatory budgeting allows citizens to influence local budgets, helping democratise decision-making and build trust between the public and government (Maclay, 2024). The growing demand for accountability, seen in the 2024 Kenyan Finance Bill and Nigeria’s End Bad Governance protests, demonstrates how digital tools can mobilise people and support inclusive, sustainable development.

The policy landscape for digital transformation in Africa is evolving. At the transnational level, the African Union’s Digital Transformation Strategy (2020–2030) and Continental Artificial Intelligence Strategy (CAIS) provide frameworks for member states to harmonise policies (African Union, 2020, 2024). Notable efforts are increasingly being made across AU member states to define national AI strategies (Akana and King’Ori, 2024). While most African countries have some form of national policy addressing the digital economy, the 2024 Network Readiness Index indicates that the continent still lags on the global stage (Portulans Institute, 2024).

For the continent to advance globally, strategies must push beyond just policy formulation. Although frameworks are in place, issues like infrastructure gaps, a lack of funding, and inadequate regulatory compliance persist in hindering globally competitive digital growth, as indicated by the mismatch highlighted in the 2024 Network Readiness Index. The uneven rate of national AI policy development adds to worries about regional disparities in technical development. If concerted efforts are not made to address these challenges, Africa faces the risk of expanding the digital divide both at its borders and globally.

Consequently, leveraging technology to advance civic engagement will be challenging at regional and national levels. While social media, mobile platforms, and digital forums have created new opportunities for political participation and public discourse, access and the ability to effectively use these spaces remain uneven. Due to high data costs, uneven digital literacy, and restricted access to dependable internet, many citizens find it difficult to participate (Barret, 2024). According to Mazibuko (2023), women and marginalized groups frequently encounter extra obstacles that restrict their capacity to express their concerns or have an impact on decision-making. Furthermore, the function of digital platforms in promoting transparent and accountable governance is complicated by problems with disinformation, online surveillance, and state-imposed internet limitations (Cariolle, Elkhateeb, Maurel, 2024). The potential of technology to promote civic involvement in Africa might not be realised in the absence of laws that give priority to inclusive access, digital rights, and data stewardship.

Civic Engagement in the Digital Era: Opportunities and Challenges in Africa

Digital technology has the potential to improve and create new spaces and channels for interaction between states and their citizens. It can support the efforts of governments to deliver services more efficiently and transparently. This will not only bring the public closer to the decision-making process but also foster greater engagement and trust in state institutions and democratic decision-making.

Participatory budgeting for instance in Kenya empowers residents to participate in local budget allocations (Maclay, 2024). However, developing and expanding such mechanisms requires investment and commitment to ensure accessibility in multiple local languages. Also, measures must be put in place to avoid co-optation by more powerful interest groups.

Beyond the more state-sanctioned participatory spaces, social media has emerged as a powerful mobilisation and participatory tool. Social media platforms are globally reshaping grassroots activism. Movements such as Kenya’s 2024 #FinanceBillProtests and Nigeria’s EndSARS campaign demonstrate how digital platforms amplify public discourse in the demand for accountability. Digital activism helps in amplifying civic voices, beyond local context and traditional media, to expose corruption and human rights abuses. However, the rise of internet shutdowns and restrictive cyber laws poses significant threats to participating in these spaces. As such, governments must ensure policies uphold digital rights and refrain from repressive online policies. Instead, collaboration with technology companies should be pursued to safeguard platform security and prevent misuse.

Additionally, the potential of digital technology in advancing civic engagement extends beyond activism to practical governance solutions. Crowdsourcing platforms like Ushahidi demonstrate the power of citizen-led data collection in tracking governance failures and service delivery gaps (Ushahidi, n.d). By institutionalising such ideas within governance frameworks, citizen-reported data can translate into timely government action informed by contextual needs.

Lastly, E-government platforms such as Rwanda’s Irembo illustrate how digital transformation can improve access to public services and reduce bureaucratic inefficiencies (Irembo, n.d). However, the effectiveness of such platforms depends on widespread internet access and digital literacy; otherwise, else access and usability end up becoming inequitable. Bridging the digital divide through targeted literacy programs and affordable internet access will ensure that e-government initiatives are inclusive and accessible to all citizens.

Rethinking Democracy in Africa’s Digital Future

Africa’s democracy and government could be reimagined with the help of digital technologies. Given the continent’s urban and demographic forecasts, technology can contribute to the realisation of a more dynamic and inclusive future. If intentional efforts are made to address current and potential barriers to digital transformation, digital tools can present a unique chance to rewrite the narrative of governance, even as issues like inequality and lack of adequate infrastructure continue to be major obstacles.

African nations are capable of advancing strong democracies that are meaningfully participatory. It is not a matter of whether Africa can capitalise on digitalisation to govern, but rather of how it can take advantage of this chance to rethink and remake democracy for the future.

Africa’s digital revolution is distinctive in large part because of its grassroots creativity. It is crucial to look inward for solutions and innovations rather than focusing too much on global trends, as demonstrated by platforms like Ushahidi that arise out of contextual necessity. Importantly, if digitisation is to truly transform government, it must strive to address community needs. Policies that prioritise digital access, digital literacy, ethical behaviour, and the preservation of online rights and freedoms are necessary to prevent advances in technology from exacerbating already existing imbalances.

African nations are capable of advancing strong democracies that are meaningfully participatory. It is not a matter of whether Africa can capitalise on digitalisation to govern, but rather of how it can take advantage of this chance to rethink and remake democracy for the future.

References

African Union. (2020). The Digital Transformation Strategy for Africa (2020-2030) | African Union. https://au.int/en/documents/20200518/digital-transformation-strategy-africa-2020-2030

African Union. (2024, September 4). Africa Urban Forum: Co-creating solutions to make cities habitable for the growing population. https://au.int/en/pressreleases/20240904/africa-urban-forum-co-creating-solutions-make-cities-habitable-growing

Akana, C., & King’Ori, M. (2024, November). The African Union’s Continental AI Strategy: Data Protection and Governance Laws Set to Play a Key Role in AI Regulation—Future of Privacy Forum. Future of Privacy Forum. https://fpf.org/blog/global/the-african-unions-continental-ai-strategy-data-protection-and-governance-laws-set-to-play-a-key-role-in-ai-regulation/

Barrett, G. (n.d.). The digital divide in sub-Saharan Africa: A barrier to quality education and information access. Bizcommunity. Retrieved February 12, 2025, from https://www.bizcommunity.com/article/the-digital-divide-in-sub-saharan-africa-a-barrier-to-quality-education-and-information-access-019625a

Bekele-Thomas, N., & Westgaard, S. (2024, October 4). Unlocking the potential of Africa’s youth. Africa Renewal. https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/october-2024/unlocking-potential-africa%E2%80%99s-youth

Cariolle, J., Elkhateeb, Y., & Maurel, M. (2024). Misinformation technology: Internet use and political misperceptions in Africa. Journal of Comparative Economics, 52(2), 400–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2024.01.002

Ibrahim Mo Foundation. (2024). Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG) 2024. https://mo.ibrahim.foundation/our-research/iiag

Irembo. (n.d). IremboGov. IremboGov. https://irembo.gov.rw/home/citizen/all_services?lang=en

Kamana, A. A., Radoine, H., & Nyasulu, C. (2024). Urban challenges and strategies in African cities – A systematic literature review. City and Environment Interactions, 21, 100132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cacint.2023.100132

Maclay, L. (2024, July 17). Participatory Budgeting is Key to Good Governance in Kenya. Center for International Private Enterprise. https://www.cipe.org/blog/2024/07/17/kenyas-2024-finance-bill-participatory-budgeting-is-key-to-good-governance/

Mahugu, J., & Mambo, S. (2024). (PDF) Real-Time Smart Road Traffic Flow Management System in a Developing Country. ResearchGate. 1st African Transport Research, Cape Town, South Africa. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/379259894_Real_Time_Smart_Road_Traffic_Flow_Management_System_in_a_Developing_Country

Martin, N. (2024, November 1). Harnessing the Power of Artificial Intelligence for Effective Natural Disaster Management in Africa. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/385420098_Harnessing_the_Power_of_Artificial_Intelligence_for_Effective_Natural_Disaster_Management_in_Africa

Mazibuko, A. (2023, May 31). Africa’s Digital Gender Divide. ACCORD. https://www.accord.org.za/analysis/africas-digital-gender-divide/

Portulans Institute. (2024). Network Readiness Index 2024 (Network Readiness Index, p. 284). Portulans Institute. https://networkreadinessindex.org/analysis/#theme

Twinomurinzi, H. (2024). From Tweets to Streets: How Kenya’s Generation Z (Gen Z) is Redefining Political and Digital Activism. African Conference on Information Systems and Technology. https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/acist/2024/presentations/13

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (2024). World Population Prospects 2024 | Population Division. United Nations Publication. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/world-population-prospects-2024

Ushahidi. (n.d). Crowdsourcing Solutions to Empower Communities. Ushahidi. https://www.ushahidi.com//